You never know when a chance conversation will change the course of your life.

It was the year 2000, and I was attending the International Health and Medical Media Awards, better known as the FREDDIE’S, in New York City at the Pierre Hotel. Attending the so-called “Oscars of Medicine” were almost 1,000 journalists, producers, film makers, and pharmaceutical and advertising executives. I was there to accept a FREDDIE for my CNN report “A Baby by Design,” which celebrated the emergence of genetic testing and cautioned against the potential abuse of this technology in reproductive medicine.

At this black tie dinner, I struck up a conversation with the man seated next to me, who worked in the pharmaceutical industry. As we were talking about genetic diseases, I mentioned that I had Wilson disease, and he knew about penicillamine, the drug I was taking. It was dangerous to take for a long time, he said, because it could lead to serious long-term side effects. I told him I had been lucky – that I’d been taking penicillamine for 17 years and was in excellent health, without any bad side effects

He was concerned enough to persist. “Wilson’s can actually be treated with zinc supplements,” he told me. “There’s a researcher at the University of Michigan who has been studying it.” As a reporter I couldn’t help but wonder if he had a vested interest in the new finding. He told me he had simply read about it, and said he’d mail me some information.

A few weeks later, a large envelope arrived at my CNN office, filled with copies of research information from this pharmaceutical “good Samaritan.” The studies suggested that zinc supplements could be used in Wilson’s patients who had been “decoppered” with a drug like penicillamine. Penicillamine binds copper in the body and eliminates it through the urine. Zinc binds with copper from foods in the intestines to prevent it from re-accumulating in the body.

It sounded too good to be true – an inexpensive mineral supplement that could be bought off a pharmacy shelf could treat a fatal disease with almost no long-term side effects? I needed to find out more.

I called the primary researcher, Dr. George Brewer, who was a geneticist at the University of Michigan. My CNN credentials helped me get through to him quickly, and he told me that zinc had been approved by the FDA for maintenance therapy in Wilson’s patients in 1997.

Then I told him that I had the disease myself, and that I took penicillamine. He was incredulous. “You’re a crazy person to still be taking it!”

Was Dr. Brewer right? To find out, I called Dr. Irmin Sternlieb, with whom I’d had a medical consultation with about five years earlier. He was a hepatologist in New York City and he had studied penicillamine extensively.

“You’d be a crazy person to switch to zinc!” Dr. Sternlieb said.

Now what? I needed a third opinion — from someone who wasn’t involved with studying either drug. So I found a hepatologist here in Atlanta, and he said most doctors still considered penicillamine to be the “gold standard” for treating Wilson’s.

Just like in the early days of penicillamine, zinc therapy still had its doubters and critics. Zinc research was still limited, with the largest study including only 141 patients, followed for 10 years or less – not enough information to change how all doctors treated their patients. In medicine, change typically occurs slowly. And I was doing well with penicillamine, so there was no need to rock the boat.

Four years later, though, the long-term side effects of using penicillamine finally started to catch up with me. I needed surgery for gum disease that was likely linked to penicillamine. My primary care doctor even suggested I call the Wilson’s expert, Dr. Sternlieb, to find out if I should cut back on my medication before surgery, since it also interferes with wound healing.

I tracked down Dr. Sternlieb in a nursing facility in southern California. “How did you find me here Rhonda?” I told him that’s what reporters do! And when I asked about my treatment, he said, “Why don’t you switch to zinc?” I reminded him that four years earlier, he had told me I would be crazy to take zinc. But there had been a sea change. “We now have enough long-term research with zinc therapy,” he said, “that I think it’s safe to switch.”

I switched to zinc, and not long after my gum disease healed.

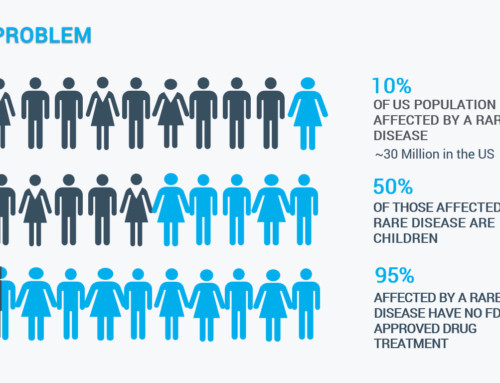

If I hadn’t had that chance conversation in 2000, or if I didn’t have the skills I honed during my many years as a CNN medical reporter, I wonder what course my treatment would have taken. Like many medical breakthroughs, some of our discoveries about our own medical care depend on chance and serendipity. Eventually, maybe medicine will evolve to the point where we can rely a little less on luck and dinner partners for matching patients to effective treatments and cures — especially those with rare diseases.