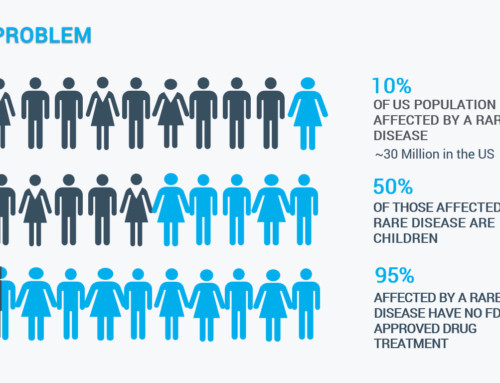

I’ve spent my career reporting medical news. It’s an important topic to me because I live with my own health challenge: A rare, genetic condition called Wilson disease that allows copper – an essential dietary mineral – to build up in the liver and brain, leading to copper poisoning that can be fatal. It caused my liver to fail when I was a college student. But I was lucky — I was diagnosed, there was a treatment, and it worked.

Before 1955, my disease was fatal. Then, through a series of chance events and serendipities, an English physician, Dr. John Walshe, discovered a drug that turned Wilson disease (WD) into one that could be treated and managed. The drug is known by its generic name, penicillamine, and the brand names, Cuprimine and Depen.

While doing research for a book I’m writing on WD, I discovered that Dr. Walshe is still very much alive and well at age 98. So I traveled to Cambridge, England to thank him for saving my life and talk to him about his drug discovery.

He invited me to his home, which is a William and Mary style house built in the late 1600’s, in the riverside village of Hemingford Grey, near Cambridge. Talking in Dr. Walshe’s quintessential English garden, it didn’t take him long to attack the pharmaceutical industry that now sells the drug that he discovered and tested.

“The way they’re charging for it now is absolutely immoral. There is no other word for it,” Dr. Walshe told me. “It is totally immoral. It is business at its worst!”

For more than 20 years I took Cuprimine and never paid more than $60 a month for it. Today, it costs $31,426 a month making it the 13th most expensive prescription drug in 2018.

Discovering the first treatment for Wilson disease

Listening to the story of Dr. Walshe’s drug discovery, it’s easy to understand why he’s incredulous about its cost.

The story began in 1954, when Dr. Walshe traveled to the United States for a Fulbright Fellowship in Boston. “I was working with Charlie Davidson who was a liver doctor, and we were asked to see a Wilson disease patient who had gone into liver failure,” said Dr. Walshe.

They couldn’t do anything to help the patient then, but crossing the “bridge” from what was then Boston City Hospital where the patient was being cared for, back to Thorndike Laboratory where he worked, Dr. Walshe had what he calls as inspiration: “I said to Charlie Davidson, ‘You know what this chap really needs is penicillamine.’ And Charlie Davidson said ‘What’s that?’ I told him I discovered this new amino acid that had never been seen in human urine before,” said Dr. Walshe.

Previously, while working in London during the early 1950’s Dr. Walshe had studied laboratory samples from people who were given the antibiotic penicillin. He observed that penicillamine – a derivative of penicillin – binds with copper. It’s a process called chelation. His theory was that penicillamine could search out the excess copper in people with Wilson disease, bind with it, and then remove it from the body through urination.

Proving his idea

To test his theory, Dr. Walshe obtained some penicillamine from a chemist at MIT. Then, he did what would be unheard of today – he tried it on himself first. “It didn’t do me any harm and the next day I was alive and well,” he said. “I decided if it was safe for me, it was safe for the patient.”

Dr. Walshe gave penicillamine to the WD patient — who was in liver failure at Boston City Hospital — and as he predicted, it got copper out. When his fellowship in Boston ended, he returned to London with a small supply of penicillamine to continue his experiments there.

“My father was England’s leading neurologist at the time, and I asked him to find some Wilson disease patients for me to try it out on,” said Dr. Walshe. His father came through with a handful of patients, and in 1956 Dr. Walshe reported in the American Journal of Medicine that his drug discovery worked.

After that, Dr. Walshe searched for chemical companies willing to make penicillamine so the new treatment could be made available to WD patients as soon as possible. This was years before the start of the current FDA drug approval process that requires costly and extensive testing before a drug can be considered for marketing.

Developing an alternative

As word spread that there was a treatment for Wilson disease, doctors started prescribing penicillamine for their patients. However, as more patients took it, they found that some developed severe side effects. So, Dr. Walshe looked for a second option.

“We had run into trouble with penicillamine, and I wanted an alternative treatment,” said Dr. Walshe.

By this time he was working at the University of Cambridge, and one morning he ran into a biochemist named Dr. Hal Dixon. Dr. Walshe explained his predicament and Dr. Dixon pulled a chemical called triethylene tetramine off his laboratory shelf.

“He said it was non-toxic and known to bind with copper,” said Dr. Walshe. “He told me to try it and that’s how we got the drug trientine. It was Hal Dixon’s idea, and my work proving that it worked and it was safe.”

Walshe made the drug himself

For years, Dr. Walshe and his assistant made trientine in their laboratory until they could no longer keep up with demand. Dr. Dixon had explained how to purify the chemical so it would be safe to use in people. So, as he had done with penicillamine, Dr. Walshe searched for a chemical company to make and distribute trientine. In 1985, trientine became the fifth drug approved through the Orphan Drug Act.

“The trouble now is the people who make trientine behave so badly about pricing,” said Dr. Walshe. “No doubt about it, they have behaved appallingly badly about pricing.”

Univar Europe charges the UK’s National Health Service the equivalent of $96,000 to treat a patient for a year. Because of the high cost, the NHS debated whether or not it could continue paying for the drug in 2019. The North American company Valeant Pharmaceuticals – now Bausch Health – charges even more for its brand-name version, Syprine.

Investigating high drug costs

In 2016, Senator Susan Collins (R, Maine) launched a bipartisan investigation into the extreme spikes that were being seen in drugs that were off-patent. “For example, the price of a Valeant drug that is used to treat Wilson disease,” said Collins, “increased from $652 per month to more than $21,000 per month. That’s more than a 3,000 percent increase in price with no justification.”

“It’s monstrous, it’s iniquitous what they’re charging for it,” said Dr. Walshe. For several years he made trientine in his laboratory. “I sent it out for free on my basic laboratory expense allowance without upsetting it. It was cheap!”

In the United States, Bausch Health now markets Syprine (the brand-name version of trientine) as well as Cuprimine. The company acquired both drugs in 2010 and, soon after, boosted the prices astronomically. Despite extensive adverse publicity, a Congressional hearing, and the addition of generic equivalents the company has yet to lower the drugs’ unjustified cost.

Walshe never profited from his drug discoveries

It’s been almost 65 years since Dr. John Walshe had his “inspiration” while walking across the bridge at Harvard. I asked him where the idea came from. He simply pointed to the sky and posed the rhetorical question: “Where do ideas come from?”

Dr. Walshe’s discovery of penicillamine and the development of trientine turned Wilson disease from a death sentence into a treatable disease. Today, the challenge for patients is not finding treatment, but being able to pay for it. Dr. Walshe says he never made any money from the two drugs, instead devoting his medical career to helping people with WD.

His idea saved my life. Now with the prices being charged for his discoveries, will others be so lucky?